GSE scholars introduce a new generation to a touchstone text on the nature of education in a modern democratic society

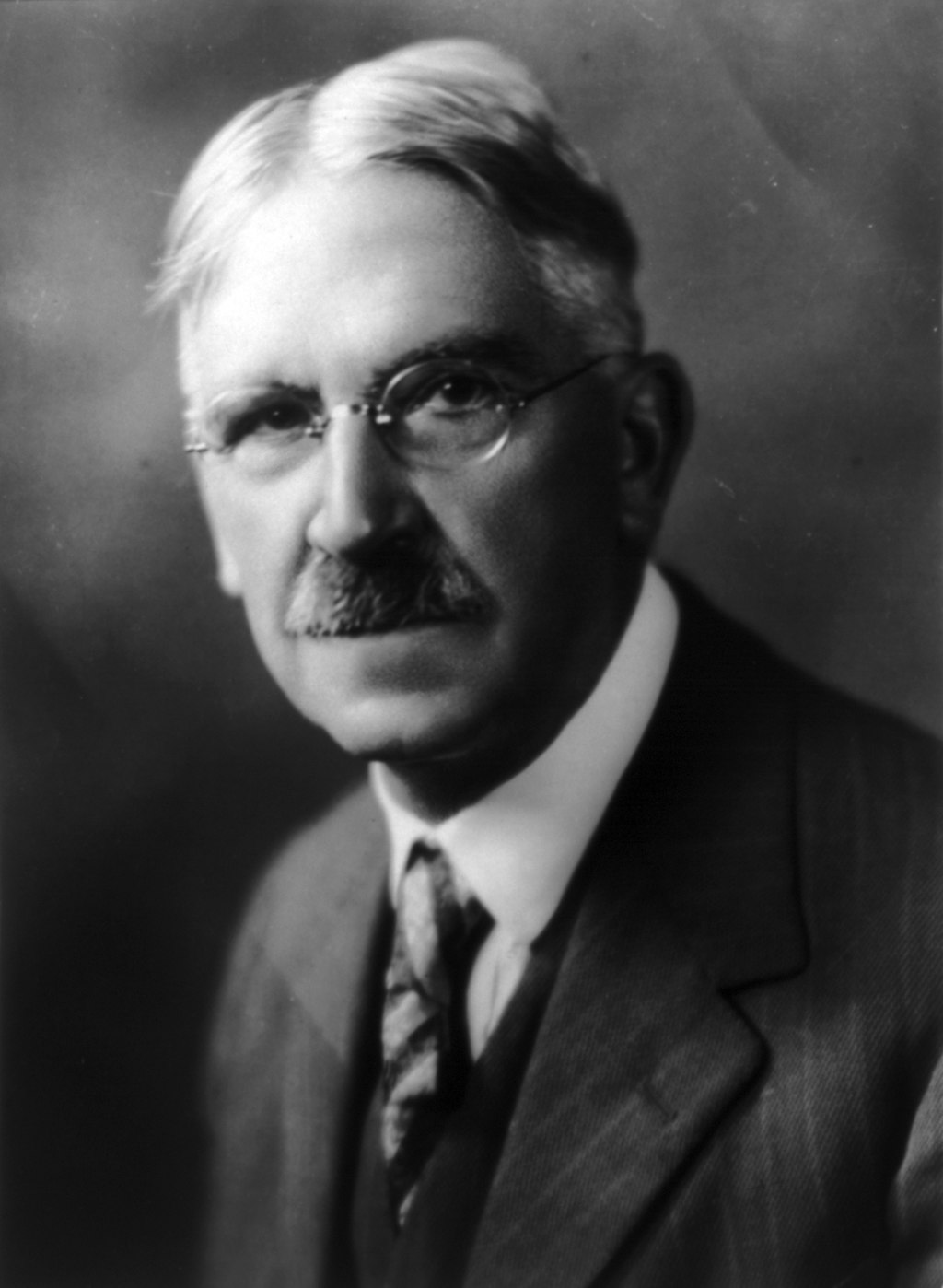

A philosophical text published 102 years ago offers vital perspectives on 21st-century learning, say three Stanford Graduate School of Education scholars who are reintroducing one of philosopher John Dewey’s classic works to Stanford students.

Dewey (1859-1952) was a prolific writer whose insights continue to shape how educators think about schooling. Yet his prose is dense and often difficult for today’s readers to understand, said Education Professor Ray McDermott, who with two colleagues is offering a Winter 2018 course on Dewey’s Democracy and Education, a 1916 book widely considered the most comprehensive and influential text on using the ideas implied in democracy to solve educational problems.

In the course, Education 397A, open to undergraduate and graduate students, McDermott said, students will learn how a great thinker framed the big issues they will contend with as educators. These include theories of cognition, choosing pedagogy, crafting aims and outcomes, and the value of universal, common schooling in shaping happy, productive people and societies.

Above all, McDermott said, Dewey explains why public schools are essential to democracy.

Library of Congress

“He said a lot of things we still need to hear about making our schools sane, safe places for children to learn,” McDermott said. “He was terrified that public schools would close down, that not everyone would learn enough to participate in society.”

The course is appropriately being offered during the celebration of the GSE’s centennial year, when the school is revisiting its research and societal contributions to public schools and the public good.

Education 397A originated in a sort of book club that McDermott and Eric Bredo, PhD ’75, hold weekly to discuss issues in educational philosophy. They were joined last year by Emeritus Professor of Education and Philosophy Denis Phillips, who published a 2016 companion guide to ease readers’ path into Democracy and Education. All three scholars will be involved in the Winter 2018 course.

“I found students need a fair bit of help to penetrate Dewey,” said Phillips, who taught a course in Dewey at the School of Education for more than 30 years until his retirement in 2007. “The way he brings things up in his 19th-century style is unfamiliar to us.”

How is a writer so difficult so influential? “It’s the breadth of his writing,” Phillips said. “The fact that he gives a theoretically coherent framework with which to tackle educational issues keeps people turning to him.”

As a contemporary of Charles Darwin and Karl Marx, Dewey studied the societal impact of industrialization, the rise of the experimental method, and the perspectives offered on education by the then-new fields of evolutionary biology, sociology and anthropology. While Dewey saw industrialization and experimental science as the major shaping forces of his lifetime, he argued that students learn best the way pre-industrial youth learned trades in family enterprises – experientially and with purpose.

“Dewey hates drudgery. Hates memorizing. He calls it ‘mere learning,’” McDermott said. “He uses the word ‘learning’ only 800 times in 37 volumes. Half of them are attached to the word ‘mere,’ by which he usually means learning of the ancients.

“In contrast, Dewey saw education as organizing conditions for change. When we coordinate the ways we change with each other, that’s a good foundation for democracy.”

Despite his challenging prose, decades of educators have cited Dewey and been inspired by him to create reforms. Academic databases reveal that writers have cited him more than 30,000 times.

Stanford Education Professor Paul Hanna, such an admirer that he co-founded a John Dewey Society, rewrote K-12 social-science curriculum to help children navigate change, and his organizational principles are still used today. Hanna hired Frank Lloyd Wright – another devotee of Deweyan concepts – to build his revolutionary Hanna House on campus in line with Deweyan principles of social learning. Later, Stanford Professors Nel Noddings and Elliot Eisner drew on Dewey's legacy in their own contributions, respectively, in the ethic of care in education and in learning as embodied in the arts.

Dewey was even honored in 1968 with a U.S. postage stamp, one in a series on prominent Americans.

Ironically, though, he is not among the great educational thinkers whom GSE founding Dean Ellwood Cubberley listed on the façade of the School of Education building.

“It’s because Cubberley, who donated the funds for the building, had an incredible dislike of Dewey,” Phillips said. “Cubberley was very conservative. But by 1938, when the building opened, Dewey was recognized as America’s major educational thinker.”

By offering the course, McDermott, Phillips and Bredo hope to reintroduce Dewey’s broad perspective to educational issues and to reinforce the value of closely reading a challenging text.

“A lot of people argue what Dewey meant,” Phillips said. “Although we generally agree, sometimes the way Eric and Ray read Democracy and Education is not the way I read it.

“We have a great deal of fun arguing. But people enjoy seeing professors fall out.”

-- Barbara Wilcox