Enterprising education professor bequeathed to Stanford a Frank Lloyd Wright showplace and a growing role in U.S. and global affairs

Stanford University Archives

Nestled into a hill of faculty housing on Stanford’s Frenchman’s Lane, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1937 Hanna House is a hexagonal hive of redwood and glass.

It is internationally known -- and on the National Register of Historic Places -- as the first permanent structure Wright built on a nonrectilinear grid, ushering in a new age of spatial exploration in architecture.

Less well known today are the house’s patrons, the late Education Professor Paul Hanna and his wife, Jean. Paul Hanna, a curriculum specialist, founded the Stanford International Development and Education Center (SIDEC), a global source of leadership in learning and precursor to today’s GSE program in International and Comparative Education (ICE). His shaping of K-12 social studies into “expanding communities” seen through interdisciplinary lenses remains one of the top textbook models in its field.

For schools are tasked with more than “passing on the accumulated social habits found satisfactory in the past,” Hanna wrote in 1939, evoking his hero, educational philosopher John Dewey. Schools also serve, Hanna wrote, “as a laboratory of culture in which the culture is examined for ways of continuously improving it, not to ‘learn’ the culture but to work with culture to better it.”

Said emeritus David Jacks Professor Henry Levin, now at Teachers College, Columbia University, in 2003: “Paul contributed original approaches to social studies education and to a more international approach at a time when the Nation was inward-looking.”

“He was a go-getter. He was one of the most entrepreneurial faculty that I have encountered here, and that is saying something,” said emeritus Professor Hans Weiler, who stayed in the Hanna House with his family when first hired by Hanna in 1965.

Today, Hanna’s house is the most visible legacy of Hanna’s Stanford years. In it, we see how fervently both he and Wright thought education could shape the world.

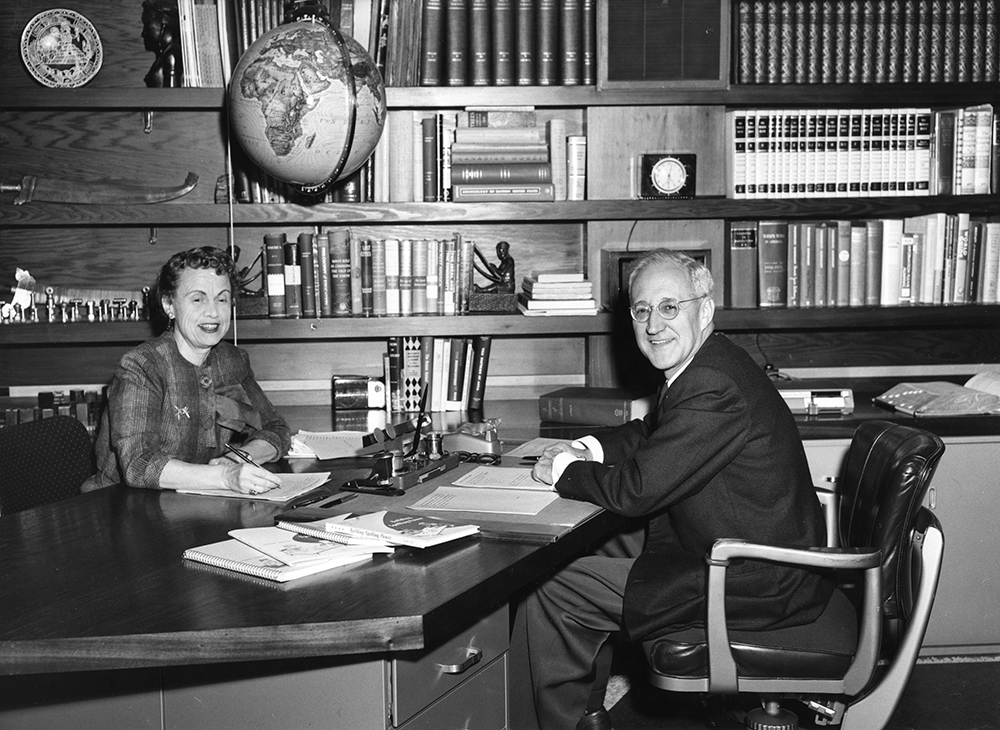

Lee Holub/Stanford University Archives

Progressive influences

Paul Hanna came to Stanford as an associate professor in 1935 from Columbia, where he had been a student. He greatly admired Dewey, whose thinking shaped the progressive education movement’s push for learning by doing, as well as toward “participation of the individual in the social consciousness” of humanity. In New York, Hanna and Jean became not only progressive educators but architecture buffs. As young marrieds in an upper Manhattan apartment, they read Wright’s Modern Architecture to each other, chapter by chapter, out loud.

Wright, too, was shaped by progressive education. His aunts ran an innovative school on the family land that became Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, where apprentices studied under the architect in experiential, interdisciplinary learning amid nature, physical labor and the arts. Wright played as a child with the educational toys called “Froebel gifts” that he later said taught him the principles of architecture.

Immediately after arriving at Stanford, the Hannas wrote to Wright asking him to build their house. The hexagonal plan that Wright produced baffled but did not faze them. In a series of collaborative exchanges with the architect, they sought that it be alterable to suit their family as it grew.

“What’s essential to both Wright’s and Hanna’s ideas of education is that people learn by doing,” said architectural historian Richard Joncas, PhD ’91, who wrote his Stanford dissertation in part on the house. “The Hannas wanted an environment in which they could raise their children according to Dewey’s principles.”

The house is built almost entirely without right angles, so that even the carpenters’ irons had to be custom-fabricated to 120 degrees. Its hexagons, Wright noted later, allow for expansion on six faces rather than four, multiplying the house’s adaptive capacity and evoking the social nature of what Wright called “those master builders, the bees.”

Paul Hanna, an accomplished carpenter, and Jean did much of the contracting themselves.

But the house’s most significant innovation in terms of educational philosophy as well as of architectural impact, Joncas said, is that Wright integrated the kitchen into the core of the house and the playroom into the adult living spaces. Wright and the Hannas called the kitchen the “laboratory,” suggesting the house as social experiment and the Hannas as social scientists.

“They could study the kids while the kids were playing in the living room. This type of treatment is unprecedented in Wright’s houses,” Joncas said.

“That was the most convincing argument to me that education was central to the house."

Stanford University Archives

Working with culture to better it

To meet the $15,000 projected cost, which soon more than doubled, Paul Hanna borrowed against expected royalties from the K-12 textbook series he planned. The texts integrate history, economics, government and geography within a matrix that starts with the family and extends outward into society, much like Wright’s honeycomb grid.

World War II greatly expanded Hanna’s own community of practice. He became Stanford’s liaison to the federal government, brokering wartime training contracts for the campus. He also began to court donors for Stanford, notably the pioneer Jacks family. His house, world-famous even before its completion, became a stunning setting for social activities. In 1954, Hanna helped acquire the School of Education’s first (and Stanford’s sixth and seventh) endowed professorships with gifts from the Jacks family.

Work in Washington exposed Hanna to America’s potential in postwar reconstruction. He built a global network of funders, alumni and other contacts. At the School of Education, he argued strenuously for additional faculty billets for international specialists. His evolving interests entailed defunding positions for elementary education, his initial specialty. Yet they aligned in many ways with Stanford’s postwar goal of creating “steeples of excellence” in a world-class research university.

Interdisciplinary model

In SIDEC, founded in 1964, Hanna united political scientists, economists, anthropologists and other discipline-based scholars in the common causes of furthering democracy through learning and of making education a catalyst of social change and development.

“He had the simple but quite ingenious plan that if you really want to do something about education and development you need to bring several disciplines together,” said Weiler, a political scientist.

“His goal was to find those who had been anointed to ascend to power in their societies, often from the elites and the oligarchies of their societies,” Levin wrote. “These were to be brought to Stanford to be educated at SIDEC and become part of an international body that was interconnected and that would work towards educational development of their societies.”

SIDEC graduates fanned out to become education ministers, UNESCO leaders, visionary educators and heads of state. They founded at least 13 university programs on the SIDEC model.

Leo Holub/Stanford University Archives

Over the years, though, Hanna grew distant from the School of Education over politics and SIDEC affiliates’ growing tendency to critique the Cold War values he believed in. He directed his papers and philanthropy to the Hoover Institution, where he and Jean endowed a fellowship on education policy.

Jean Hanna died in 1987, Paul in 1988 after leaving their house to Stanford with hope it would house scholars in international education. Instead, it became the residence of four university provosts.

Today, it is used for receptions, by arts students and scholars and for other educational purposes. Repaired after extensive damage in the 1989 earthquake, the house has undergone yet another renovation and recently reopened for tours.

“The Hanna House is one of the masterpieces of American architecture, not just because of its great beauty but because of its central importance in the work of Frank Lloyd Wright,” emeritus Art Professor Paul Turner said in 1996. “It is the classic expression of many of Wright’s design principles.”

Yet it would not exist, he said, without the foresight and cooperation of the Hannas, its clients.

“Wright’s decision to use them as guinea pigs in an experiment to build a revolutionary design was due to his knowledge of these two young people,” Turner said. “Their enthusiasm. Their idealism. Their willingness to innovate. More specifically, their ideas about education and the importance of environment in the life of a family.”

As Paul and Jean Hanna wrote, “Mr. Wright gave us a home that left an imprint on the lives of our children. They know the subtle but true relations of form and purpose, of site and dwelling. For them, beauty is a way of living.”

-- Barbara Wilcox

Read Paul and Jean Hanna’s Client’s Report on building and living in the house that “broke open the box” of traditional architecture.

Learn about Hanna House tours.

Read more about Paul Hanna’s Stanford years from his biographer, Jared Stallones.

Explore the GSE’s program in International Comparative Education.