Stanford’s Black Student Union disrupted a 1968 campus assembly with 10 demands that helped shape educational history

In April 1968, the world reeled in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. At Stanford, Provost Richard Lyman called an April 8 convocation in Memorial Auditorium to discuss “Stanford’s Response to White Racism.”

As the panelists – all white – faced the capacity crowd, 70 members of Stanford’s Black Student Union ascended the stage. They took the microphone from the provost.

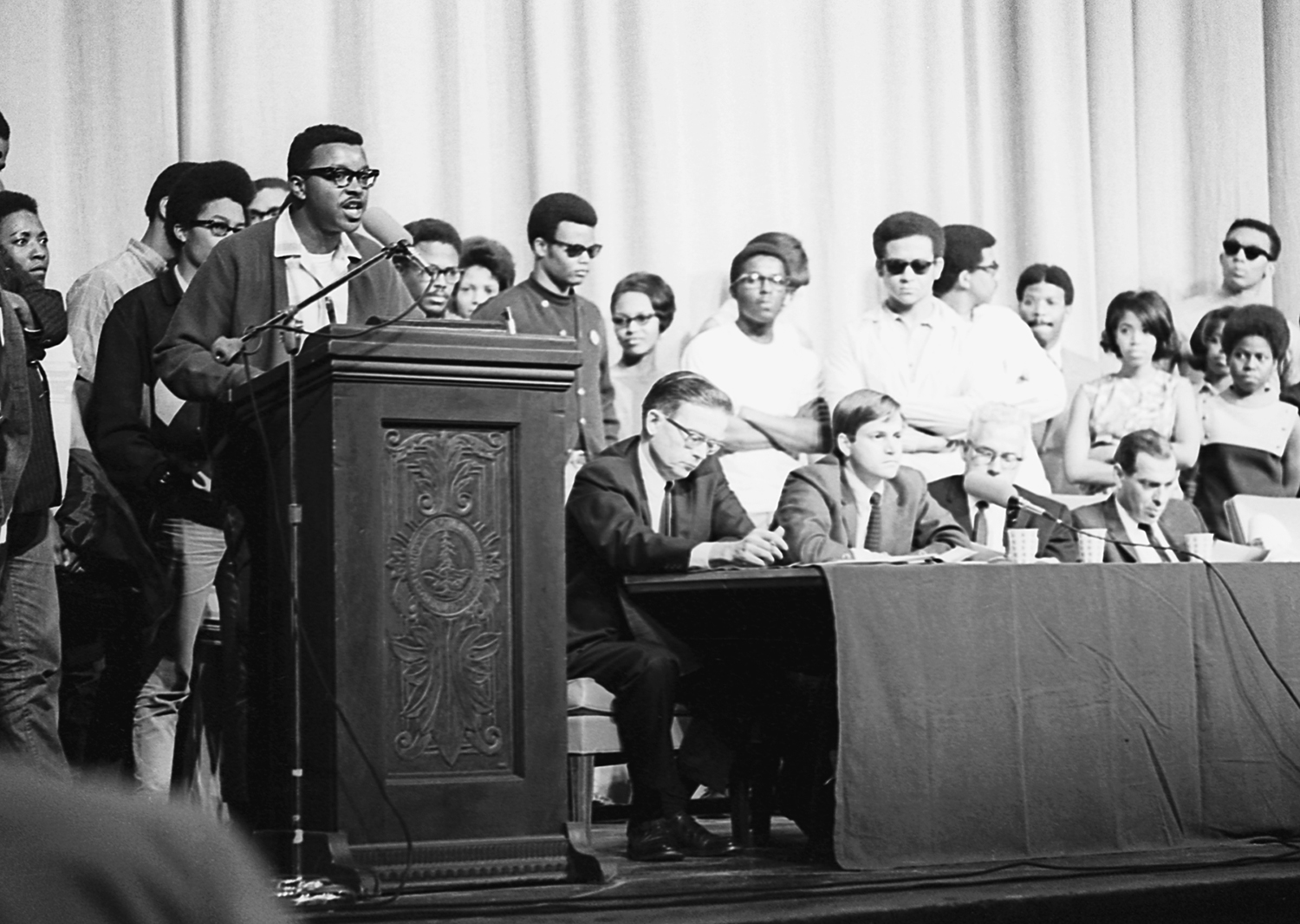

Frank Omowale Satterwhite, a doctoral candidate in the School of Education, read a list of 10 demands that he and other BSU members had crafted to boost African-American admissions, curriculum, hiring and broader representation at Stanford.

The moment’s tension can be seen in the faces around Satterwhite in a famous photo. Most of the students had never been in a direct action before.

Yet, after three days of talks, Lyman and Stanford President Wallace Sterling accepted nine of the 10 demands. They pledged within two years to double Stanford’s black enrollment – then about 1 percent of the student body. They authorized the first African and African-American Studies program at a private university.

Wrote the Black Student Union in its history for the university’s centennial, “Those demands marked the beginning of substantial progress in creating a multicultural campus community.”

Black students at the School of Education played leading roles in that moment and its aftermath. Shaping and shaped by that tumultuous era, they went on to distinguished careers in teaching, research, community-building and social justice.

“Education students were probably a ‘critical mass’ at that time, which might account for our higher numbers in activism,” says Joyce E. King ’69, PhD ’74, who helped implement the 10 demands.

These alumni caution that “taking the mic” did not stand alone, but occurred within a nexus of activism, radicalism, self-schooling and community that acted on its participants in often unexpected ways.

“Being in the Stanford environment actually transformed a lot of people into being much more activist because you saw the world of the privileged that you'd never been exposed to and understood,” Mary Montle Bacon, MA ’71, PhD (Social Psychology) '78, told the Stanford Historical Society.

Satterwhite, PhD ’77, for his part, had entered his degree path aiming to become president of a historically black college or university.

“When I came to Stanford in fall 1967, over the next 15 to 18 months I was exposed to many, many social movements in the Bay Area,” he recalls. “There was an international Pan-African movement focused on the liberation struggles in Africa. The Black Power and Civil Rights movements in the USA. The Black Panther Party. Dr. Maulana Ron Karenga and the US Organization. San Francisco State College and UC Berkeley in the Bay Area. I could go on and on.

“Well, the best way to learn a language is total immersion. I was totally immersed in the politics of the time and came out of that period radicalized.

“All of it was important to my own transformation,” says Satterwhite. “As of 1969, I was sure I would do community-based work for the rest of my life.”

The Stanford Daily

The Black Student Union, which had formed at Stanford in spring 1967, urged members to make a connection with the community of East Palo Alto, then about 65 percent African-American. One way, says Satterwhite, was to tutor in both public and what the era called independent (now called Afrocentric) private schools.

“Each student did what we call today a service-learning contribution,” he recalls. “That was how we as black students began to see a connection to black students in the community and throughout America and the world.”

They studied the power structure of education and how to make it more responsive to black learners. They looked at curriculum and pedagogy, since few, if any, teaching materials addressed African-American content. And they looked at Stanford, which had only one black fulltime faculty member – anthropologist James Gibbs – and where the few black students and visitors endured, as Joyce King recalls, “blatant racist incidents.”

King had come to Stanford from very modest means in Stockton, Calif. On her first visit to campus, she looked up a student who was from her church.

“I went to her residence on the Row, looking for her. And the people there told me they didn’t know who she was. I finally found her in the library, and I went into the library to bring her greetings from home. She looked at me and all she said was ‘Ssssshhh.'

“I thought to myself, ‘If I come here, I don’t want to be like that.’

“That was my first encounter that was a warning: This is not a safe place to be.”

King remembers that in her freshman year, 1965, the university began to admit more black students – maybe 25 a year, in contrast to the three or four of years prior. This was still a tiny minority, but, along with other social changes, it began to inspire alternatives to the outcome King feared – of becoming so acculturated for survival’s sake that she would become “totally disconnected from the people who raised me, who sacrificed for me.”

The Black Student Union tried without result in 1967 and early 1968 to air its concerns with Stanford leaders. The day after the Rev. King's assassination, days before “taking the mic,” members burned a U.S. flag on White Plaza in frustration and rage.

In an atmosphere of great tension, Satterwhite and others on a committee drafted the 10 demands. He credits the demands’ cogency not to his education studies but to the advice of co-chairman Charles Countee, '67, who had done direct action before.

“The first draft of demands – there might have been 30 or 40 of them,” Satterwhite remembers. “Countee said that was too many demands. We had to regroup them.”

Sterling hailed the result as “the basis of a constructive program of action.” But the students’ work had only begun as they strove to secure a lasting commitment from the university.

They helped interview and select an assistant provost for minority affairs, becoming the first Stanford students ever involved in that level of hiring.

They helped to run a small program for experimental admissions – demand No. 7 – in which 10 students of color entered Stanford each year despite not meeting usual criteria.

Education Prof. Robert Hess helped advise this effort by Stanford to increase and retain a more diverse student body. Joyce King, an undergraduate sociology major, was hired by the university president’s office to help run the program.

“I had an expense account and a car,” she says. “I traveled to the students’ homes. I drove to the high schools. I talked to their counselors. I talked to their families … all to ease their transition into Stanford.”

Three years after the program was launched, nine of its 10 inaugural admits remained in good academic standing.

Some came from Nairobi College, a community school in East Palo Alto that many of the Stanford students helped to run. Among its leaders was Warren C. Hayman, who earned his MA in math education at Stanford and, after decades in educational leadership, now sits on the Community College of Baltimore County Board of Trustees.

Satterwhite kept organizing, with a detour to establish the black studies program at Oberlin College. His work informed his Stanford dissertation, advised by Prof. Lewis Mayhew, on “Black Power and Education.”

“The social and educational environment of Stanford had virtually no relevance to the African-American experience,” Satterwhite says. “That came out of my own lens.

“But I took a number of courses on research design and evaluation, on organizational management and on educational psychology … That baseline knowledge I gained at Stanford gave me the grounding to move to the top of my profession as a grassroots community management consultant.

“It has had infinite value.”

Joyce King received Stanford’s Dinkelspiel Award for her contributions to student life. She went on to become provost of Spelman College, holder of an endowed chair at Georgia State University and president of the American Educational Research Association in 2014-15. Her books include Black Education: A Transformative Research and Action Agenda for the New Century and Dysconscious Racism, Afrocentric Praxis and Education for Human Freedom.

“Before, you were supposed to almost blend in to the point of disappearing,” King says. “There were black students ahead of me who did that. I was concerned about those I would leave behind.

“We have helped to make space for a different way of knowing, a different way of being in the world.

"That’s my generation’s contribution.”

-- Barbara Wilcox

Learn more:

Read Black70, an African-American Stanford yearbook edited by Joyce King in 1970.