Graduates of one Stanford School of Education master’s program found new ways to expose new audiences to the joy and discipline of movement

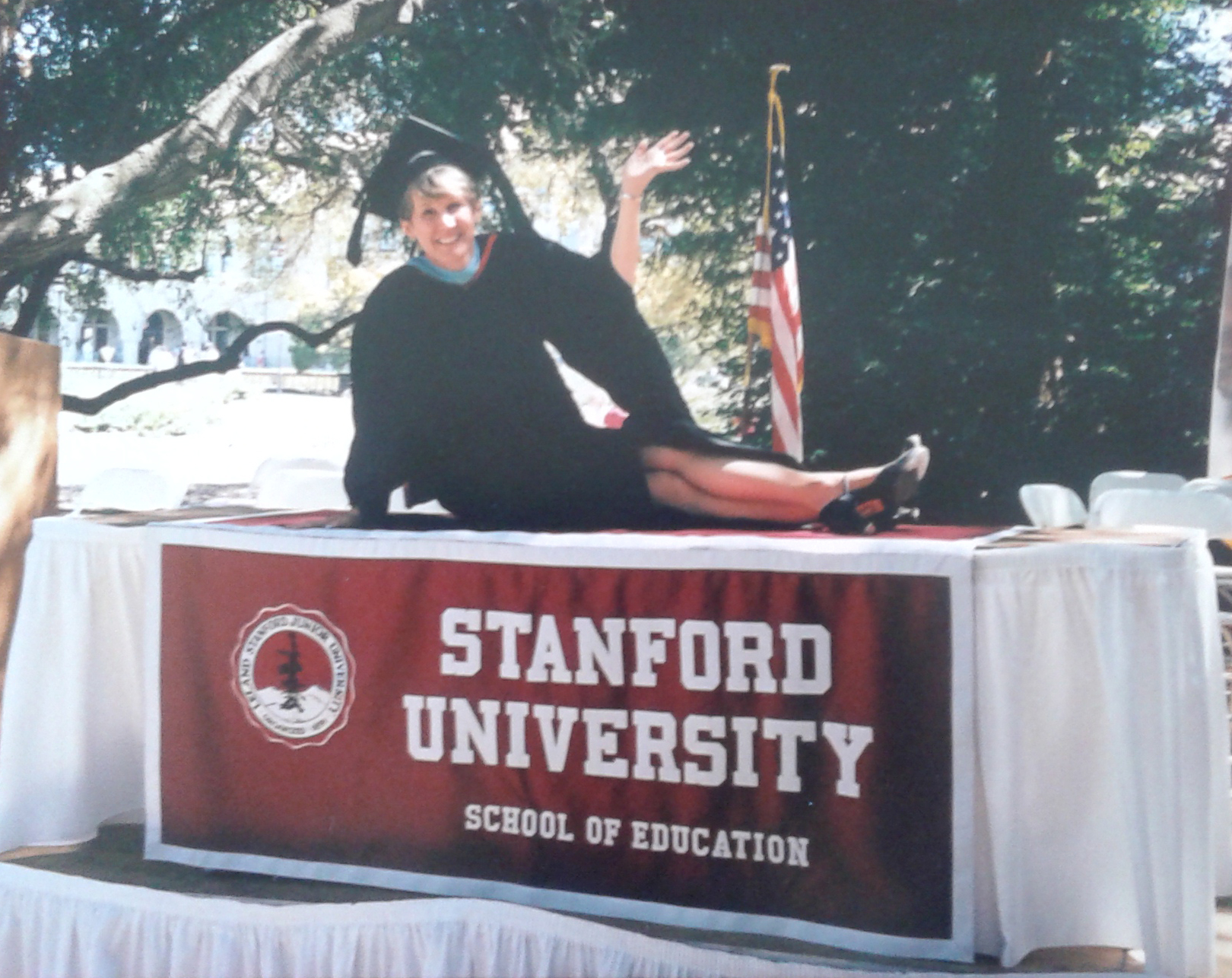

Dance teacher Joan Walton was 43 years old when she closed up her Cincinnati apartment in summer 1998 and drove across the country in her Honda del Sol convertible to attend Stanford.

“Give me a quiet roommate,” she asked Stanford Housing. “I have a lot of work to do.”

Walton, MA ’99, says her life was transformed by the School of Education’s small but influential master’s program in dance education. From the early 1970s to 2003, this program trained teachers of many dance forms to broaden their sensibilities, their pedagogies and their audiences as part of a push to elevate arts education.

Many graduates found jobs in higher education, boosting the rigor of dance studies and helping move them from a recreational to an academic realm. Some founded college departments or dance companies.

All explored new ways to teach and learn movement, broadening access to dance by making it accessible to more people.

They helped shift dance from what the program’s guiding light, Prof. Elliot Eisner, called the “null curriculum” -- content that is not taught but which helps define education by its absence -- into the actual curriculum, where its history, content and pedagogy stand toe-to-toe with those of the humanities and other fine arts.

“Elliot loved the kind of mind that got developed through a physical arts practice,” said his student Prof. Janice Ross, MA ’75, PhD ’98, now a professor in Stanford’s Department of Theater and Performance Studies.

“He was a Deweyan through and through. He felt [John] Dewey’s theory of ‘knowledge acquisition through doing’ was fully embodied in dance, which remakes the maker through the act of pursuing movement.”

Stanford University Archives

How the program got started

Since 1911, when dance classes were first taught in the Department of Athletics, dance has been part of Stanford. In 1928, Big Game Gaieties featured Creation: A Ballet of Machinery, a work choreographed by English Prof. Harold Helvenston and starring Jeannette Owens, ’29, as “the completely awakened machine whose power is stronger than itself.”

Dance’s fortunes rose at Stanford in correlation with rising enrollments of women, says Ross, a dance historian. In 1931, the university relaxed its 500-woman cap on undergraduate enrollment instituted by co-founder Jane Stanford.

The move immediately added nearly 350 women to the student body and raised demand for curriculum traditionally undertaken by women. Roble Gym for women opened that year with what Ross calls “one of the most magnificent dance studios in the West.”

In 1973, Stanford ended all gender-based enrollment curbs in the wake of federal Title IX. This antidiscrimination law also led to an upgrading of women’s athletics, which eventually left Roble and diverged from dance in the Stanford curriculum.

Around the same time, Education Prof. John Nixon, who taught physical education and sociology of sport, and dance instructor Inga Weiss structured a separate dance degree in the master’s in arts education offered by the School of Education’s Curriculum Studies and Teacher Education.

Changing the artist's perspective

No more than four students were admitted into the program each year. Many were decades out of college.

“I had a large gap between grad and undergrad, as dancers often do,” Walton says. “They’re out there spending their bodies when they’re young.”

They embraced all aspects of Stanford life.

“I wrote home, ‘I think they’ve injected caffeine into the atmosphere. Everything is so exciting,’” Walton remembered.

“The whole atmosphere of the school helps you remake who you are, how you present yourself to the world.”

Students took one course per quarter in the School of Education with Eisner and Prof. Larry Cuban.

"Perspective changes incrementally. The artist may succeed in maintaining a vision of the whole, or get lost in the brush strokes.

Students also took dance theory and practice and the history of performance art, as well as dance ethnology with the late Prof. Susan Cashion.

Walton’s capstone project was based on Howard Gardner’s seven intelligences. She examined how people can learn to dance mathematically, musically, linguistically, kinesthetically, visually, intrapersonally or interpersonally.

“All of the ed students were constantly together, irrespective of their background,” recalls ballet teacher Kasey Church Brown, MA ’03. “You might collaborate with someone from an entirely different background – maybe they had been a math professor. It was challenging. But it helped me get concepts across to students. I use that now.”

So did teaching ballet fundamentals to Stanford students whose challenges despite obvious intelligence and drive revealed the limits of a conventional approach.

“I would ask myself, ‘What’s a better way to say this to someone who’s used to dealing in numbers?’” Brown recalled. “In dance we are constantly using music and counts. Maybe I can explain a move in terms of counts and numbers.”

Brown came to Stanford in search of a better ballet pedagogy.

“Ballet is a little behind in its teaching methods,” she said. “There is a mentality that you’re a little mean. And none of its methods is terribly effective.

“In my training, I came from a studio where the director was a taskmaster. We were all really afraid of her. She had her favorites. And she had her people whom she’d use to illustrate what not to do.

“That is a teaching method. We paid attention. But I wanted to teach in a more positive way.”

The cohorts acquired new teaching strategies adopted from groupwork, breaking classes into pairs to work on steps and technique. They developed strategies for positive correction.

Alumni impact

Today, Walton lectures at San Jose State University and teaches movement at the College of San Mateo. More than 120 SJSU students yearly take her Dance and World Cultures for humanities credit, writing papers on dances of their culture of origin.

Bubba Gong, ’79 (Economics), MA ’92, founded the dance program at Foothill College. Committed to diversity and inclusion, the program has given thousands of people a performance stage and brings world-class companies to the region.

A pro dancer from childhood, Gong won a nationwide search to become a Disney World “Kid of the Kingdom.” Bernadine Chuck Fong, BA ’66, MA ’68, PhD ’83, former Foothill College president and now Stanford’s associate vice provost for graduate education, saw Gong perform “Singing in the Rain” at Great America and hired him, while he was still an undergraduate himself, as Foothill’s tap-dance instructor.

For her part, Ross was instrumental in moving dance education at Stanford from the Department of Athletics to the School of Humanities and Sciences’ Department of Theater and Performance Studies (TAPS).

“Graduate degrees are very important at Stanford,” TAPS professor emeritus Bill Eddelman told the Stanford Historical Society. “Her PhD helped bring the two together in terms of academic respectability.”

The move legitimized dance as an art practice, Ross told the society: “It changed the frame of how the university approached dance, and dance, as a result, became much fresher and more deeply artistic.”

The dance-education MA ended in 2003 amid changes in School of Education leadership and vision and an economic climate that put pressure on arts teachers.

“It reached the point that it wasn’t really tenable,” Ross said. “It’s an expensive master’s degree. The pool of people who could manage that really diminished.”

Its influence remains, at Stanford and elsewhere, as its graduates produce an ever-widening pool of dancers, teachers and devotees.

“Dance education is basic education,” Gong said. “Dance clarifies and intensifies the human experience.”

-- Barbara Wilcox

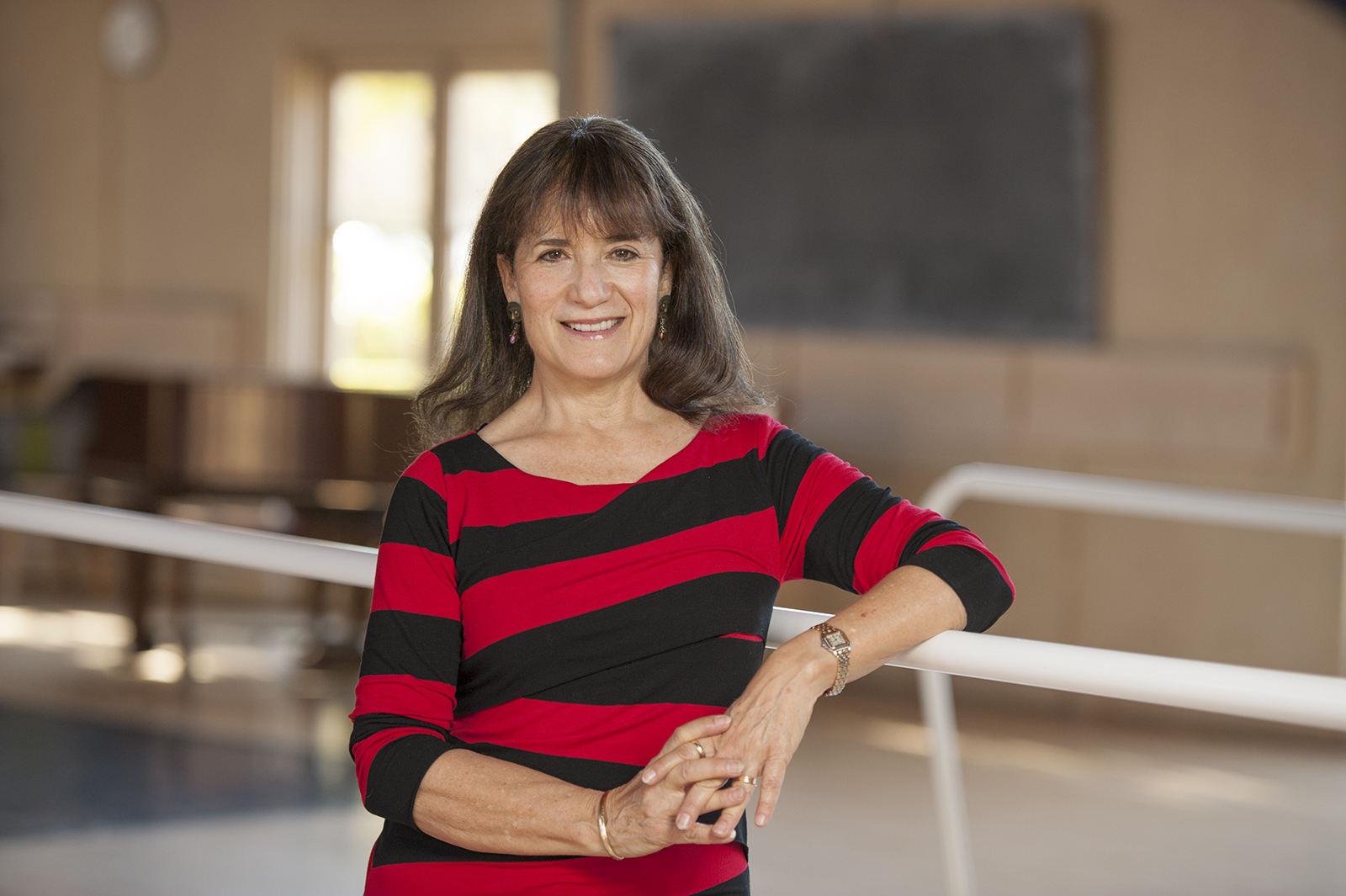

Top photo: Janice Ross, MA ’75, PhD ’98, professor of dance in Stanford's Department of Theater and Performance Studies, in Roble Gym before its 2016 renovation. Credit: Linda A. Cicero, Stanford News Service