One far-reaching School of Education program drew its impetus not at Stanford, in one participant’s telling, but years earlier and far away, with a five-year-old learning to ride a bicycle in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

John Krumboltz, eventually to become one of Stanford’s – and America’s – most eminent psychologists – decided one day to bike down a street he’d never been down before. There, he met a kindergarten friend whose sister had just gotten a tennis racket. John and his friend decided to learn to play.

John later made it to his college’s varsity tennis team. It was a small school, and the tennis coach also taught psychology. When John asked his coach what to major in, the coach said, unsurprisingly, “Psychology.”

Fast-forward 10 years, and young PhD John Krumboltz was recruited to the Stanford School of Education’s new program in counseling psychology by Prof. H. B. McDaniel, himself a guidance counseling pioneer. Krumboltz, his colleagues and students broke new ground by applying behavioral psychology and theories of social learning to a range of human challenges.

Prof. Carl Thoresen, PhD ’65, showed in 1983 that changing cardiac patients’ Type A behavior dramatically reduced risk of recurrent heart attacks and improved long-term survival. Prof. Teresa LaFromboise in 1996 published a life-skills curriculum that reduces hopelessness among Native American teens, whose risk of suicide far outstrips the U.S. average.

Stanford Educator

Krumboltz, who led the program after McDaniel’s death, capped his own distinguished career with the 1999 Happenstance Learning Theory that revolutionized career counseling. Rather than helping people make career decisions, he helped them to derive lifelong benefit from largely unplanned events, just as Krumboltz did with his bicycle, his tennis and his coach.

Today, GSE-trained psychologists continue to improve health, social justice and wellbeing by finding new ways to teach resilience, self-care and resistance to harm. From the School of Education’s programs in counseling psychology, which ran from 1959 to 2009, and now in Development and Psychological Sciences, they extend educational interventions from the classroom into the world.

The achievements seem diffuse, but, as Krumboltz likes to say, “It’s all connected if you look backward.”

Better living through learning

“People often ask, ‘Why is counseling psychology in a school of education?’” observes Margo Jackson, PhD ’99. She replies:

“Clinical psychology focuses on a deficit model, looking at what’s going wrong,” says Jackson, now a professor in the Fordham University Graduate School of Education.

“Counseling psychology focuses on a learning model. It addresses the part of an individual’s behavior that is within his or her control.

“It’s a holistic model that fits well in schools of education that concentrate on learning in the community and in social justice. It’s all toward the common goal of helping people develop their full potential all over their life span.”

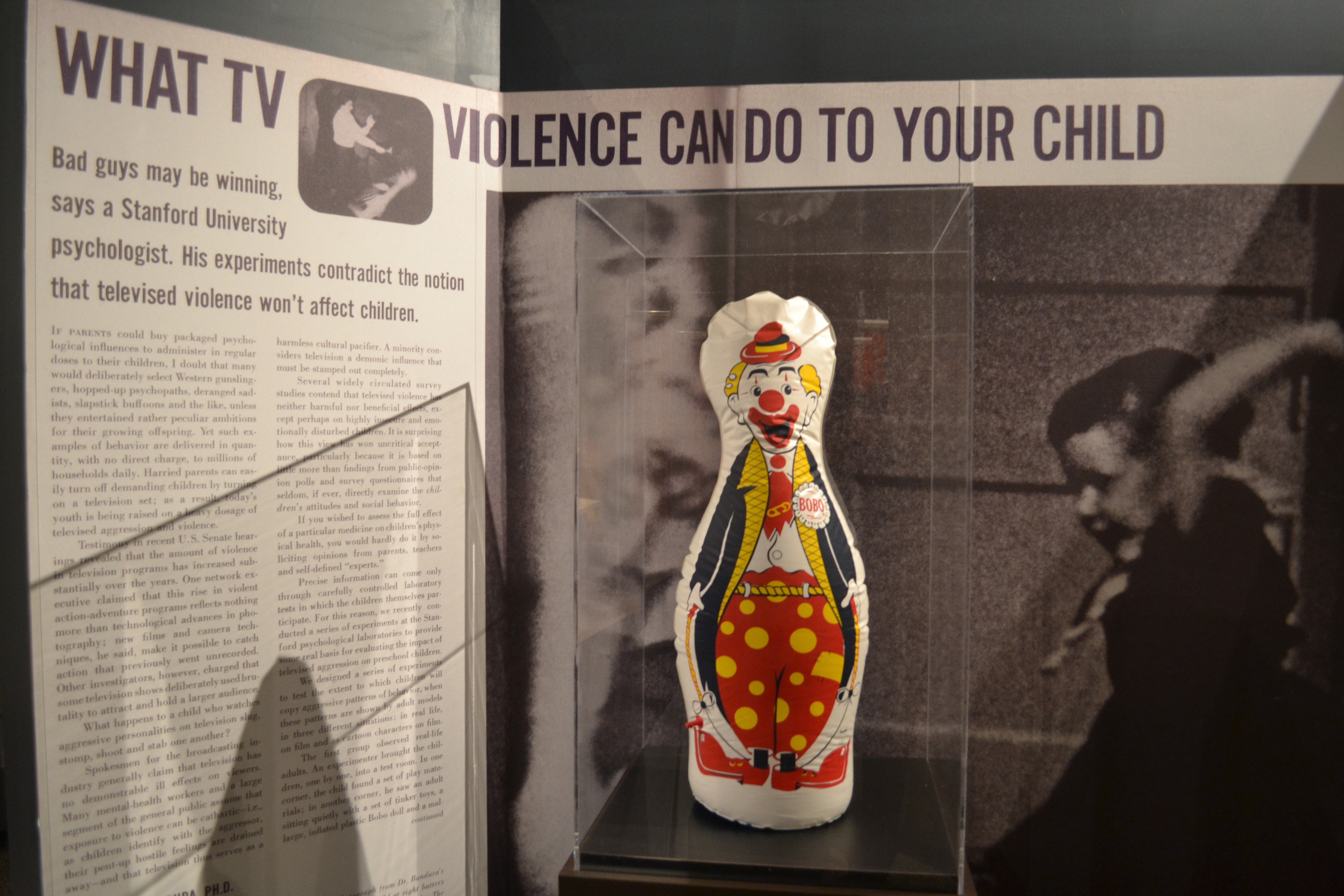

Drs. Nicholas and Dorothy Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron

Carl Thoresen, as a San Jose middle school counselor in the early 1960s, sought out McDaniel in search of better counseling techniques and wound up in the doctoral program.

“I told him, ‘I like the kids and the parents but I don’t know what I’m doing,’” Thoresen recalls.

“He said, ‘Not many people would say that about themselves. I like that you haven’t studied psychology. You haven’t been brainwashed.’”

Both Krumboltz and Thoresen built on the work of Stanford psychology Prof. Al Bandura, whose famous study of Bing Nursery School kids venting rage on Bobo the Clown gave rise to the social theory of learning. Bandura revealed that without the rewards or punishments that behaviorists like B.F. Skinner thought were required – simply by watching and learning – people could readily change their behavior for good or for ill.

Krumboltz’s and Thoresen’s great advance was to harness this power of social learning for good.

“Al Bandura allowed me to think, ‘Yes, chart behavior but also cognitive phenomena, attitudes,” Thoresen said. “For me, Stanford just brought Skinner and Bandura together. It was very, very exciting, because it was new territory.”

Thoresen first became known for helping insomniacs get more sleep. In the late 1970s, he got a call from Dr. Meyer Friedman, a cardiologist at San Francisco’s Mount Zion Hospital who thought that behavioral change might offer patients help in the days before statin drugs and other medical advances.

Thoresen’s Recurrent Coronary Prevention Project assigned 862 heart-attack patients one of two treatments. The first group attended informative sessions on diet, exercise and medication. The second attended small-group counseling designed to change their Type A behavior: excessively competitive, time-urgent, hostile and aggressive.

The patients who received behavioral counseling were 44 percent less likely to suffer a second heart attack within the 4.5-year study period, and 24.6 percent less likely to do so in the three years after the study ended. They were less likely to die of other causes as well.

“I would say that was the most significant experience in my life,” Thoresen says.

“I would say my father was a Type A. He died a very young man. By the way, most of the people in the study were in their early 50s. In those days, if you had a heart attack and you survived, the chances were that if you had another, 60 percent of the time you’d die.

“Technically, if you’re heart’s working, if your brain’s not fried, technically you’re alive. But it’s not the quantity, it’s the quality of life.”

Understanding history, understanding self

LaFromboise, who came to Stanford in 1985, studied how social skills training for bicultural competence – in both mainstream and ethnic/tribal worlds – could help Native American high school students resist substance abuse, suicide and other self-harm.

Her American Indian Life Skills Curriculum, developed with Zuni Pueblo and Cherokee Nation educators, among others, offers lessons in resilience that are grounded in Native American culture. Participants learn to value their own and their community’s good qualities. They learn to cope with the historical, social, and individual stressors that fuel a Native American suicide rate up to 72 percent above the U.S. average.

In the semester-long program, students learn strategies for taking control of their thoughts and feelings, for saying no to drugs or alcohol, for coping with grief and loss. They learn how historical events such as their parents’ or grandparents’ suffering in federal Indian boarding schools or their tribe’s loss of land due to settler colonialism bear on their own lives, for, as one lesson explains:

“Losing freedoms such as land … is much like losing a relative. There is a sense of loss, of sadness, depression and anger. … These feelings are natural. Yet if they go on too long, they become unhealthy. … If you understand your history, you will better understand the pressures that surround you … By understanding these pressures, you can begin to overcome them.”

Finally, students learn to “create and talk about dreams for Native American people that can make us strong.”

The curriculum has been shown to decrease feelings of hopelessness and suicidal thoughts in high school-age participants. It has been modified for several other Native American communities and for use in middle schools.

GSE-trained psychologists have found other ways to help people live better lives.

Jesus Manuel (Manny) Casas, PhD ’75, helped develop the field of Latino psychology. He is lead editor of the Handbook of Multicultural Counseling, now in its fourth edition (with Jackson as co-editor) and the most internationally cited resource in its field.

Casas has worked with Fortune 500 companies to increase their sensitivity, knowledge, and practices in regard to the growing Latino/a population. After more than 30 years at UC Santa Barbara, he retired as one of the senior Latino faculty members in the University of California system.

Among his many activist volunteer activities on behalf of Latinos here and abroad, Casas helped the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala to develop the first Ph.D.-level counseling psychology training program in Guatemala.

Marc Franklin

Norm Robinson, PhD ’74, became Stanford’s longtime associate dean for student affairs. He helped make campus housing a learning environment for social plurality and healthy identity formation. On Robinson’s watch, Stanford in 1990 became one of the first U.S. universities to open its married-student housing to gay and lesbian couples.

Fred Luskin, PhD ’98, documented the healing power of forgiveness. Leonard Beckum, PhD '73, updated San Francisco's police exam to improve entry-level hiring of minorities and pave the way for women to serve in street assignments.

Cecil Reeves, PhD ’78, was one of the first scholars to chart the effects of racism on black men’s health. William Conwill, PhD ’80, wrote an ethics curriculum for African-American teenagers. Bernie September, who was brought to the U.S. in a program to prepare black South Africans for post-apartheid leadership, became an advocate for women’s empowerment and a board member of South Africa’s largest bank.

The common thread to all these achievements is providing not advice, but education. As Thoresen says, “To educate is to change.”

“The whole purpose of research is to have an effect on other people,” Krumboltz said in accepting the American Psychological Association’s 2002 award for distinguished contributions to knowledge.

“Who becomes a counselor?” he asks. “Someone who wants to help people, who doesn’t have all the answers, but wants people to take action to get there, to find out.”

-- Barbara Wilcox

Top image: John Krumboltz and graduate students test one of Krumboltz's career-beliefs assessment tools in an undated photo.