Psychologist Thoresen is best known for establishing that changing Type A behavior in cardiac patients reduces their likelihood of recurrent heart attacks. A first-generation college student, he earned his PhD from the School of Education’s program in counseling psychology and became a professor in the program.

I went to Cal. Class of ’55. I was a crew athlete, a jock. I was in a fraternity. I didn’t know what to major in. Then I got a note: You have to declare a major or we’re going to fine you $35. I thought, “Holy shit.”

I’ve always loved history. I took a course as a freshman with Kenneth Stampp, an expert in the antebellum South. He didn’t read; he told stories. It was fascinating. So I majored in history. I got highest honors.

My adviser said, “We want you in our doctoral program.” I said, “I don’t want to be a historian. I like the stories.”

It’s a lonely business, history. It’s all very, very introverted. I was very extroverted. They sit in the library by themselves and read all these things. It’s boring.

He stopped me at the door and said, “How are you going to get a job with a BA in history?” Then he added, with disgust, “You could go over to the School of Education and get a credential.”

So I walked over to Haviland Hall and said, “I want to teach.”

I taught for five years in a San Jose middle school, athletics and math. Another teacher told me, “You know, Stanford will allow you on Saturday mornings to take courses in the School of Education for free if you’re a public-school teacher. What do you have to lose?”

I don’t think I had ever been on the Stanford campus except for the stadium for Big Game. Had to ask people where SUSE was. I go into Cubberley and no one’s there. It’s about 9 a.m. on a Saturday morning. I started wandering around. All the doors were closed except one. I could see a light and I pushed the door open.

I saw a tweed jacket. Feet up on the roll-top desk. Smoking a pipe. It was H.D. McDaniel. Dr. Mac. He was the one who went up to Sacramento in the 1930s to require that to be a psychological counselor in schools you had to have specialized training in psychology, not just a credential.

I peeked in the door. If you have an image of a professorial type, he was it.

He asked what I was doing at the time and said, “Come over here and shake my hand. You’ve survived. I admire that.”

Marc Franklin

At that time, psychology was so theoretical. Freudian. A lot of words. So I really respected B.F. Skinner’s ideas: Why don’t we really get down and talk about what you do and say? We don’t need all these theories – they can be logical, but where’s the empirical evidence? He said, You have to change the behavior.

Most psychologists thought Skinner was treating people like rodents. You can stimulate or punish the animal, and the animal’s behavior will change. A lot of people think these [interventions] are really Orwellian. But to me it was stimulating.

In the 1970s, I created a program in Palo Alto for wards of the juvenile court who had been classified as out of control. “Incorrigible” was the term. I worked with Michael Wald, a law professor at Stanford whose specialty was children’s law.

Mike told me, “They warehouse these kids.” Well, I had kids myself....

Mike called Grace Mitchell, president of a women’s group in Palo Alto. Mrs. Mitchell had heard about Skinner. She gave us seed money.

We found a two-and-a-half-story house in the middle of Palo Alto. Right across the street from Channing House. Built in the 1880s. It had huge oak trees and a big swing. There was a mom-and-pop store right next to the house.

What we were simulating was a family with a mother and a father and six kids.

We did that for five years starting in 1974. It was a big success. Then, in 1979, the funding that we got from San Mateo and Santa Clara counties was lost and the house closed down.

Half of the kids we got couldn’t read. My wife, Kay, was a veteran third- through sixth-grade teacher with a master’s degree in reading. She created a tutorial and would come and teach every other afternoon.

We had a time-out room. If the kid got violent and really screwed up, we’d put him in there. It was the pantry. We had to build a door that the kids could not kick down. But there was no physical punishment.

Some of our doctoral students were married. If they didn’t have kids, I trained them to be surrogate moms and dads. They were on duty for two weeks and off duty for two weeks. And we had a point system for the kids. If you wanted to watch TV, you had to have the points. It was very, very concrete. You don’t hit anyone. You don’t use certain words. Doing so would cost you points.

One of my doctoral students got interested in the program’s cost-effectiveness. He determined that the juvenile detention facility in Stockton cost $34,000 per year per kid. The cost of Learning House was something like $9,000.

All of these kids, legally, were wards of the juvenile courts. We worked with Palo Alto police, who were required to know their whereabouts.

We had one 12-year-old boy who looked like he was 18. Very street smart. We called him Johnny the Jumper. He’d break out of anything. His parents refused to talk to him.

One day Johnny the Jumper decided to leave. He left a note, saying “Don’t worry. I want to travel.” Thumbed his way to Chicago. In Chicago, he called us long distance, saying, “Don’t worry, I’m coming home.”

He’d learned responsibility to feelings.

I think he was gone for about three weeks. Every few days he called in on his way back to Palo Alto. We’d notify the local police wherever he was, as was required by the courts.

He knocked on the Learning House door one night at 11 p.m. One of the teaching parents got up and let him in.

He said, “It was fun, and then it was very lonely.”

Another kid was a fire maker. No one told us that this kid had gotten in trouble for lighting fires. He started a fire in the church, I think it was the Presbyterian Church. It was quickly put out. But he never started a fire in Learning House.

-- Barbara Wilcox

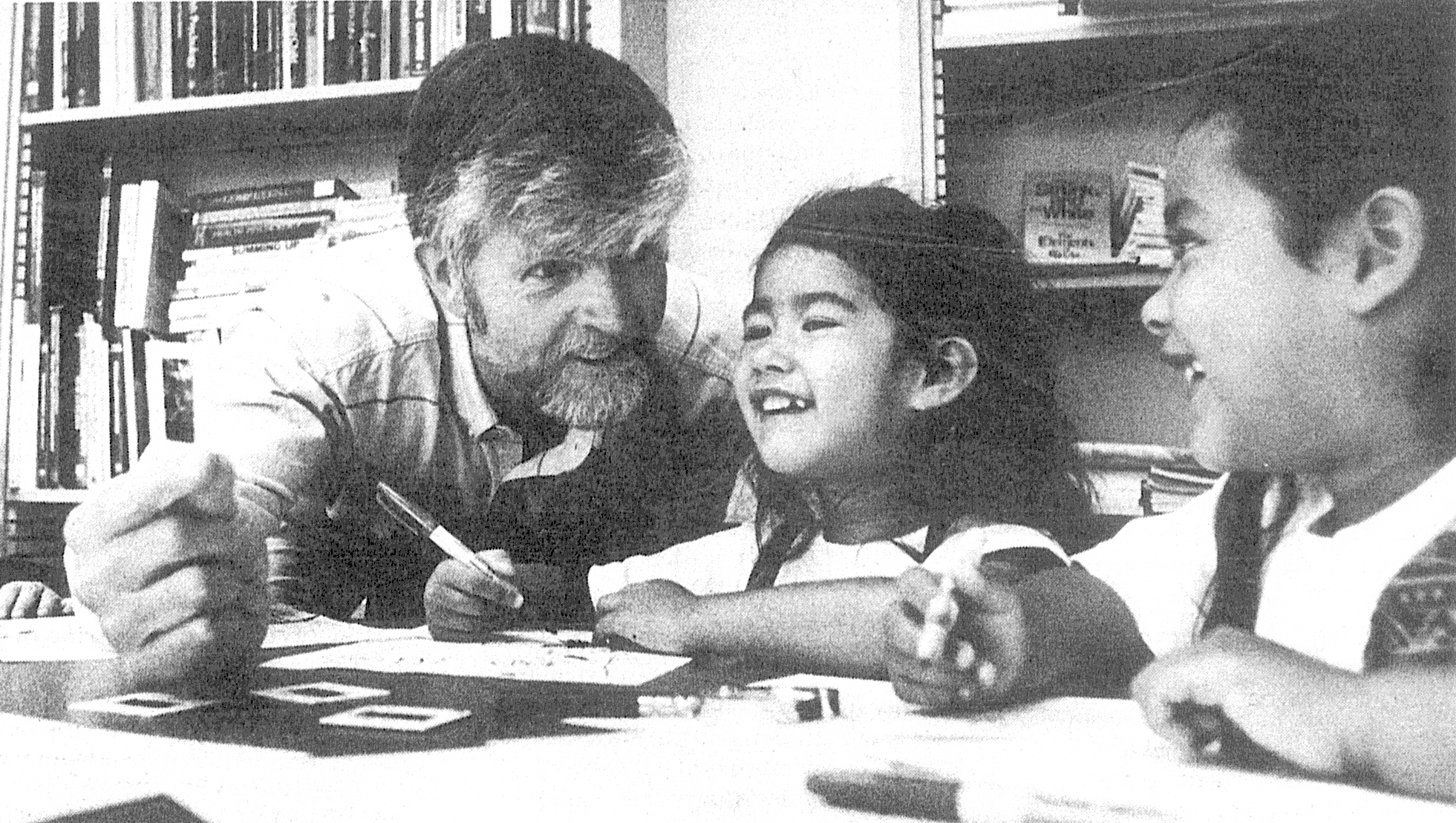

Top photo: Thoresen with local kids in 1991. Renee Burgard/Stanford Educator