Stanford-trained educator took the 1960s revolutionary spirit to remarkable lengths and inspired thousands to teach for empowerment and equality

University of Massachusetts Amherst College of Education

Dwight Allen, ’53, MA ’57, Ed.D ’59, may be best known for co-inventing microteaching, a process for training teachers involving short cycles of teaching, feedback and re-teaching. He not only completed all phases of his higher education at Stanford, but launched his faculty career here as well.

Allen was founding director of teacher education for the Stanford Teacher Education Program (STEP), launched in 1959. He yoked the School of Education’s historic pursuit of educational efficiency, launched in the Cubberley era, to his own time’s emerging technologies and passion for social change.

“My lifetime aspiration was to be a tenured professor at Stanford,” Allen said. “A year after I got tenure, I left. Life plays tricks on you.”

As dean of the University of Massachusetts Amherst College of Education, he radically and controversially overhauled curriculum, staff and admissions to to boost African-American enrollment and to send experimentally minded educators into public K-12 classrooms and other positions of educational leadership.

At Stanford, Allen led one of the first efforts to videotape student teaching and to computerize high-school scheduling. He was an early proponent of magnet and charter schools, of project-based learning and the idea of “differentiated staffing,” in which teachers of varied skills and training take on different roles.

David Berliner, PhD ’68, calls him “one of the most admirable and creative educators I have ever worked with.

“Not only did he help launch my career, but as one interesting idea after another tumbled forth from him, he provided the challenge to us to evaluate the latest of the ideas that he offered,” Berliner said. “The research community is still trying to catch up to him, a special man, with creative ideas and a lifetime of commitment to making education better for all.”

Jay Becker/Stanford Daily

Allen grew up outside San Francisco, the son of a successful auto dealer. Both his parents were Bahá’ís, a faith Allen said has always steered his work and values. On missionary trips, the Allens introduced the Bahá’í faith to Swaziland and founded schools there.

As an undergraduate, Allen managed the Stanford Band and choreographed the 1952 Rose Bowl halftime. He ran Stanford’s World Relief Club, staging a fundraiser in which students paid to have Stanford professors wait on them at dinner.

“When I was an undergraduate, they said you should never do your graduate work where you do undergrad,” he said. “But I loved Stanford and was doing things I enjoyed.

“Doing my master’s degree, I decided that education didn’t make any sense,” he said. “That teachers were all interchangeable parts, that they were at the bottom of the totem pole, that the emphasis was on facts, not on context. I thought that American education needed a complete do-over.”

Joining Stanford’s faculty in 1959, Allen looked for ways to increase the rigor of teacher preparation and to empower teachers as individuals.

“Most people agreed that student teaching was the most powerful part of teacher education, but professors didn’t like to supervise practice teaching," he said. "They didn’t want to have to go off campus.”

Originally using audio recordings, Allen and education Professor Robert Bush's microteaching evolved around 1960 into an early application of video. Allen’s project bought the first commercially available portable videotape machine – “Or it was called portable, anyway,” Allen said. “We used a trailer to pull it around so we could record student teachers in actual schools.

“In microteaching, you concentrate on a single concept lesson," he said. "It was originally 15 minutes; later we made it five. That way, you could have teaching, critique, re-teaching and re-critique within a single 50-minute period. You had both feedback and the ability to do something with the feedback in real time. Our research showed that even with the five-minute format, the opportunity for immediate feedback followed by a timely re-teaching of the lesson led to significant improvement in teaching performance.”

Stanford University Archives

Later, the video component was dropped and the peer-feedback aspect refined.

Bill Toomey, MA ’64, who went on to win the 1968 Olympic decathlon, said being Allen’s student was "a turning point" in his life.

“It helped me come to view my training as an organizational pursuit of excellence, almost like starting and running a small business,” Toomey told the Stanford Daily in 1996. “You have to investigate what you hope to get out of it, find out what you need to get started, learn to organize your time, monitor your activity, and so on.”

Allen was recruited away from Stanford by Charles F. Kettering II, whose family foundation had funded much of his research.

“On the plane [to the UMass interview] … I was still convinced I had no interest. But then I thought, wouldn’t it be better if I changed my attitude to explore what it would take to make me interested. With that epiphany, I started drawing up a list of requirements - that I be allowed to hire 15 new faculty members in my first year; that as dean I’d have a nine-month annual contract allowing me freedom to continue my work with outside schools and to travel internationally; that they’d move my executive assistant from Stanford, that the traditional admissions requirements would be waved for a significant number of doctoral students -- to name a few.

"I had heard that public universities had very narrow rules and conservative hiring practices. I wanted to test whether I’d really have the latitude and the resources to make a difference.”

It was 1968. Allen was 36 years old.

“At the interview, the provost looked down, read the list and said, ‘What else do you want?’ I felt completely hoisted by my own petard."

At UMass, Allen abolished letter grades and prerequisites and rewrote the course catalog. He gave doctoral students full voting rights as faculty members.

“I was looking for young people who had a revolutionary spirit and who would enjoy having responsibility before their time. Nate French, for example, didn’t have a PhD or even a master’s. But he’d helped to found a school called Black Mountain College – a milestone in experimental education. So I hired him as an associate professor with tenure.”

During Allen’s nine-plus years as dean, the UMass School of Education became recognized as a hotbed of innovative activity, preparing approximately 800 doctoral students who shared their own brands of innovation and social justice around the globe.

“My goals are absolute, but my means are flexible,” he said at the time, a quote beloved by both his admirers and his critics.

Allen left UMass in 1978 to join Old Dominion University with the appointment of University Professor. He worked with UNESCO and the World Bank in southern Africa and China. He helped launched teacher training colleges in Lesotho and Botswana and brought microteaching to a newly independent Namibia using a discipline he called "2 + 2": two compliments and two suggestions for improvement.

“Only 40 percent of teachers in Namibia had completed junior high school,” Allen said. “They needed a teacher training program that could be administered in the field. Some of these classrooms were at the end of a 100-kilometer track in the desert.

“So I changed the model to allow teachers to evaluate each other.”

Allen then brought microteaching to China, making 53 visits in all.

“I dropped out five years ago when I had my stroke,” he said. “But at one point, 750,000 teachers in Hunan Province were using 2 + 2.”

Now 86, Allen reflects on his career.

"From an early age I was raised to believe in the oneness of humankind and that achieving freedom from racial prejudice was America’s most challenging issue.

“Have we made progress? Yes!... Is more fundamental change needed? Even more definitely yes!... We don’t have anything within shouting distance of equity in education, but I am optimistic that with continued hard work, we can continue to make progress.

“I will be eternally grateful for the many opportunities I have had to intervene in contemporary education systems - introducing changes – some of which have endured. Even more importantly, I feel blessed to have been able to work with so many creative, enthusiastic and courageous colleagues and students who have dedicated their lives to furthering the goal of improving education and championing social justice.”

-- Barbara Wilcox

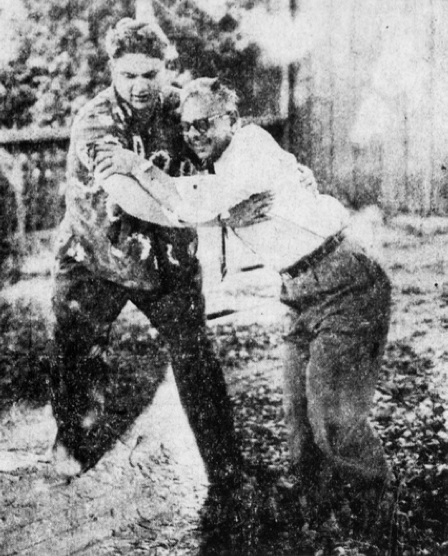

Top photo: Dwight Allen makes a statement at the University of Massachusetts College of Education in 1973. Special Collections and University Archives,UMass Amherst Libraries